This post isn't a "how-to". There are a few of these on the internet that try to show you how to make your own split nuts and some of them illustrate very dangerous methods. If you have the proper equipment (a lathe and a mill) making a few saw screws and split nuts can be fun, but you learn very quickly that the screws offered for sale by most modern saw makers are more than reasonably priced. I don't sell any because mine are patterned off of the old cast style screws with the tapered head. To seat mine properly you need a special countersink, and I don't plan on making more of them.

This is how I make the split nuts using a lathe and a mill.

The brass can be bought from McMaster-Carr in 7/16 dia. For the sake of efficiency I make them two at a time, working off both ends.

First I drill for 8-32 thread.

Tap

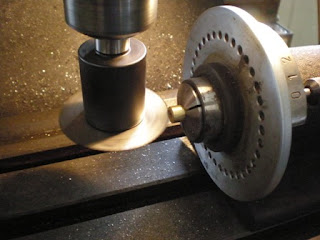

In the mill I set up a .040 slitting saw and make a cut .060 deep.

Back to the lathe where I measure back an eighth, plunge in, and back-cut the taper.

Then cut it off. In the picture above you can see I have a take-home container from some restaurant that sits nicely on the lathe bed. This collects the nuts as they get cut off and prevents me from having to dig through those nasty birds nest (probably full of tetanus) that would otherwise steal my finished product and not return it without a fight.

After that it's time for a little clean up with a belt sander and the tap. Done. Easy, if you have the right equipment. If you don't, just buy the screws. A drill press is not a mill is not a mill is not a mill, just as a chunk of railroad rail is not an anvil is not an anvil is not an anvil . . .

Wednesday, May 9, 2012

Friday, March 9, 2012

Nothing But . . .

Those last few posts might have given you the impression that the sawmaking had been on hiatus, but I posed a few of the latest projects here for proof-positive that I'm still at it. I have a fresh batch of dovetail saw backs with the new stamp folded up and I started roughing out a few more handles. The sash saw towards the center is nearly done, the handle pattern is a little later than the other styles I have been working with but I really like how it feels in the hand. All of these saws are without screws, so I'll have to whip up some of those soon. Here are three new handle patterns that I have tried.

This one has a 12" blade that I filed crosscut, 13tpi.

I've been interested to try a dovetail saw like the one in Duncan Phyfe's tool chest, the handle is set at a pretty high angle which gives it a different feel. I am really looking forward to playing with this one once I get another batch of screws done.

This is a really early style which doesn't seem to have the panache of the styles that followed, but it does look good in the hand (assuming you saw properly and get that index finger pointed out in front).

So there you have it. I'm not indulging my diversions enough to make the saws take a backseat. While I have taken a little time to play with making other tools, I am still making plenty of time to try new handle styles and having nothing but fun in the process.

Thursday, March 8, 2012

Another Preview

Sometimes I think I'm like a dog chasing cars. I look at tools and start thinking of how I would make it. Consequently, I get side tracked often, but the results are usually pretty cool. My latest detour has been infill planes because, honestly, it would be a shame to have the resources I have, and not give it a go. What I have so far is a half finished shoulder plane out of mild steel. I see no need, given what I have, to use any sort of tool steel for the body (especially on a first attempt). I know a lot of modern makers like to use it, but I wonder about the choice. Hopefully some day I'll find the time to experiment and see for myself what the pros and cons are to these choices.

Most of the metal work is done, the mouth probably needs a bit more work, but I won't know until I get a blade worked up. Below are some pictures from the peening process. That part taught me that I need to make another hammer, something similar to a filecutter's hammer. I was using a 2 lb cross peen hammer and a ball nosed punch, but I was choked way up on the handle, gripping it right under the head with fore finger and thumb. Oh well, a project for another day, I shouldn't get detoured when I'm already on a detour . . .

My other side-track, though this one is strictly and after-hours project, is an adjustable match plane by Geo Burnham Jr. This was a cheap antique store plane -no blade, no wedge, no handle, one screw arm broken and the other badly warped. I grabbed this guy because of the challenges that will come with it, and I don't feel that I'm compromising too much historical integrity on a plane that is so busted up.

I am sitting on a large pile of boxwood, thanks to my uncle who had some growing on his farm in Virginia, but I'd rather try to rehab the originals screw arms than replace them, glutton for punishment . . . I'll have to email that magician of hydro-manipulation Ed Wright and see what can be done for the bent arm.

This will definitely be the most challenging plane restoration I have done, but the reward will be a finished plane which will then tempt me to make its partner.

I promise the next post will be nothing but saws. Nothing but.

Monday, February 27, 2012

Chalco Hand Stamps

One problem I thought about for awhile was how to label my saws. Several contemporary makers use medallions, but I like the look of the stamped back better. In one of my Internet ramblings I revisited Bill Carter's site to see what he had been up to lately http://www.billcarterwoodworkingplanemaker.co.uk/. I clicked on his link to Ian Houghton's Chalco Stamp and Die Company.

If you haven't seen them yet it's worth a click. They do some very cool work in not only stamps but dies and engravings. First I ordered a "CADY" stamp.

It's a great stamp, and Ian was a great guy to work with. The stamped logo adds that extra touch to my saws. With my museum background I am very interested in an authentic look to my projects and I focus on working many elements into my saws to give them the proper look. It's the attention to detail that decides whether a saw is elegant or chunky. Quite a few saws you see being made these days don't seem interested in their lines and consequently they get fat backs, rectangular blades, and blocky handles. These elements are not without precedent, (for example take the fat backs on most Hill late Howel saws) but if you are going to the trouble to spend a few hours custom making a saw, you may as well invest a little time in making it elegant as well as functional. If you plan to hang it out for your friends to see, don't let it be a testament to your untrained eye or impatience. Beyond basic design, what truly makes any project are the details, and having a stamp like this one is the icing on the cake. I was so enamoured with the look that the CADY stamp gave to my saws that I had to order another. This one says SPRING.

Unfortunately I have a box full of backs ready for my next few saws, so the SPRING stamp won't see any use until the next run of backs I make, but I do need to crank out a few smaller ones some time soon, so stay tuned.

And check out the Chalco Stamp and Die webpage: http://www.spanglefish.com/metalstamps/

Little hand stamps like mine are pretty mundane compared to some of the other work these guys have done, click through their pages and see what I'm talking about.

If you haven't seen them yet it's worth a click. They do some very cool work in not only stamps but dies and engravings. First I ordered a "CADY" stamp.

It's a great stamp, and Ian was a great guy to work with. The stamped logo adds that extra touch to my saws. With my museum background I am very interested in an authentic look to my projects and I focus on working many elements into my saws to give them the proper look. It's the attention to detail that decides whether a saw is elegant or chunky. Quite a few saws you see being made these days don't seem interested in their lines and consequently they get fat backs, rectangular blades, and blocky handles. These elements are not without precedent, (for example take the fat backs on most Hill late Howel saws) but if you are going to the trouble to spend a few hours custom making a saw, you may as well invest a little time in making it elegant as well as functional. If you plan to hang it out for your friends to see, don't let it be a testament to your untrained eye or impatience. Beyond basic design, what truly makes any project are the details, and having a stamp like this one is the icing on the cake. I was so enamoured with the look that the CADY stamp gave to my saws that I had to order another. This one says SPRING.

Unfortunately I have a box full of backs ready for my next few saws, so the SPRING stamp won't see any use until the next run of backs I make, but I do need to crank out a few smaller ones some time soon, so stay tuned.

And check out the Chalco Stamp and Die webpage: http://www.spanglefish.com/metalstamps/

Little hand stamps like mine are pretty mundane compared to some of the other work these guys have done, click through their pages and see what I'm talking about.

Labels:

Chalco Hand Stamp

Wednesday, February 1, 2012

Spokeshaves

Another project I have in development is spokeshaves.

A spokeshave is one of those tools that you don't seem to use often, but when you do, you are very glad you have it. The only problem with spokeshaves is availability. I'm not a big fan of the metal bodied shaves of the past, even the Stanley chamfer shave I have seems to collect more dust than wood shavings. Which isn't to say that they are bad tools, they just don't seem as useful to me compared to my wood bodied shaves, given what I want them to do when. Certainly I am not alone in my feelings on the topic. Michael Dunbar said this in Restoring, Tuning & Using Classic Woodworking Tools,

Usable wooden spokeshaves are hard to find for several reasons. Because they are wood, and because many people like to use them for chamfering projects, often you will find ones where the area in front of the mouth (the wear) is troughed out. This can be worked down to true, but sometimes that opens the mouth up too much. Compounding this problem is the blade itself, which is quite short and consequently doesn't have much life.

If you true up the bed and sharpen the blade, you might have too large of a mouth to produce a fine shaving. Replacement blades are not available, in fact if you look on some shaves and their blades you might find the matching Roman numerals that some makers employed to keep the parts from getting mixed up as the shave went through the manufacturing process. Ken Hawley's book, Wooden Spokeshaves, along with being an amazing resource, indicates that this was done because of the little irregularities in every blade and the fact that every blade was uniquely fitted to a shave. When the spokeshave went to the finishing room, the blade was left behind for the final fitting that was done after the finishing process was complete.

Because the irregularities in the blades prevented them from being interchangeable, when the blade was used up or damaged beyond repair, the entire shave was trash. This isn't a great waste, the bodies are not too hard to make, and it seems that some woodworkers were involved in making their own from purchased blades.

I had a blade, and some flat-sawn beech sitting around, so I made a spokeshave. Using Hawley's book for instructions I first fitted the blade. The traditional method according to Hawley was to bore a hole for the tang on the blade, ream the hole, then drive in a square tapered drift that matched the square taper on the tangs. Using the same fixture during the blade forging process you can get a certain amount of uniformity in the taper of the tangs, how much I can't say until I've completed mine and worked up a batch. But if you make your drift using the same fixture, your pieces should be close (close enough for wood). Because the blade I had was a one-off and I didn't have a drift for it, I spent time with my needle files and small floats.

One things I have noticed on some original shaves is that some have tiny holes drilled at an angle into the mortise, from the top side. I assume this was an attempt to loosen up the fit, but was this done by the manufacturer, or done later by the user?

Once the blade fit, I was able to lay out the escapement behind the blade and open it up with saws, floats, and a mill file.

Next was the lay out of the body, similar to saw handle making -lay out some reference lines, drill a couple of holes, saw off what you can, then go at it with rasps and files. Hawley says that the old maker he interviewed used a drawknife to rough out the handles (there is a picture of this man using his drawknife in Hawley's book), and I think I will do that next time. Profiling the body of a spokeshave was quite fun. They are very beautiful tools when you stop to look at all of the lines on them.

After all of the shaping, I scraped the surfaces and shellaced it.

As with any first, this project gave me a few ideas of what to do on the next, and I think future models will feature the addition of brass wear plates will increase the working life of the body.

The purpose of the project was to determine the feasibility of making these as a saleable product. I like the idea, and if I can produce the fixtures for forging good blades, you might see spokeshaves available from me in the future.

Dubar, Michael. Restoring, Tuning & Using Classic Woodworking Tools. New York, New York. Sterling Publishing Co, 1989.

Hawley, Ken, and Watts, Dennis. Wooden Spokeshaves. The Tools and Trades History Society, 2007.

Rees, Jane and Mark, ed. The Toolchest of Benjamin Seaton. The Tools and Trades History Society, 1994.

A spokeshave is one of those tools that you don't seem to use often, but when you do, you are very glad you have it. The only problem with spokeshaves is availability. I'm not a big fan of the metal bodied shaves of the past, even the Stanley chamfer shave I have seems to collect more dust than wood shavings. Which isn't to say that they are bad tools, they just don't seem as useful to me compared to my wood bodied shaves, given what I want them to do when. Certainly I am not alone in my feelings on the topic. Michael Dunbar said this in Restoring, Tuning & Using Classic Woodworking Tools,

"The spokeshave has been used for centuries to clean up curved work or to do light shaping. Although they do not look much like planes, they are related. As occured with planes, the earlier spokeshaves had wooden bodies that were eventually replaced by those made of cast iron. However, wooden spokeshaves are far superior to metal ones (my metal one hangs on a hook and has not been used for many years). pg. 184.

The difference in performance is not related to body material, the key distinction between the two is in the blade angle. Metal bodied shaves are more often pitched at higher angles, comparable to most handplanes. Wood body blades are much more acute, usually around 22 degrees, like a mitre plane. Usable wooden spokeshaves are hard to find for several reasons. Because they are wood, and because many people like to use them for chamfering projects, often you will find ones where the area in front of the mouth (the wear) is troughed out. This can be worked down to true, but sometimes that opens the mouth up too much. Compounding this problem is the blade itself, which is quite short and consequently doesn't have much life.

|

| Used up Greaves & Sons blade |

Because the irregularities in the blades prevented them from being interchangeable, when the blade was used up or damaged beyond repair, the entire shave was trash. This isn't a great waste, the bodies are not too hard to make, and it seems that some woodworkers were involved in making their own from purchased blades.

|

| Spokeshaves from Seaton Chest. They do not appear on the purchase list with the other tools and may have been by Seaton himself. |

One things I have noticed on some original shaves is that some have tiny holes drilled at an angle into the mortise, from the top side. I assume this was an attempt to loosen up the fit, but was this done by the manufacturer, or done later by the user?

Once the blade fit, I was able to lay out the escapement behind the blade and open it up with saws, floats, and a mill file.

Next was the lay out of the body, similar to saw handle making -lay out some reference lines, drill a couple of holes, saw off what you can, then go at it with rasps and files. Hawley says that the old maker he interviewed used a drawknife to rough out the handles (there is a picture of this man using his drawknife in Hawley's book), and I think I will do that next time. Profiling the body of a spokeshave was quite fun. They are very beautiful tools when you stop to look at all of the lines on them.

|

| Profiling -notice you keep the cut-offs from the arms to help clamp the project in the vice. |

As with any first, this project gave me a few ideas of what to do on the next, and I think future models will feature the addition of brass wear plates will increase the working life of the body.

The purpose of the project was to determine the feasibility of making these as a saleable product. I like the idea, and if I can produce the fixtures for forging good blades, you might see spokeshaves available from me in the future.

Hawley, Ken, and Watts, Dennis. Wooden Spokeshaves. The Tools and Trades History Society, 2007.

Rees, Jane and Mark, ed. The Toolchest of Benjamin Seaton. The Tools and Trades History Society, 1994.

Labels:

Seaton,

Spokeshave

Tuesday, January 24, 2012

Japan Trip 2009 Part 1

It has been my great fortune to have several opportunities to meet and work with many talented persons who explore and preserve traditional crafts. From working at the Anthony Hay Shop in Colonial Williamsburg, to having a beer with Roy Underhill, to hoping a flight to Japan to spend some time living and working with swordsmith Shoji Yoshihara, I've had some fun.

Japan was probably my most intense experience. I've traveled internationally before, but never to Asia. In Europe, it seemed like I could get a feel for parts of the different languages I heard, most share certain words or wood roots, but the Japanese language seemed like white noise to my ears, and when you get off an eleven hour flight, it's mid-night at Narita Airport and you're alone, you realize pretty quickly that you aren't in Iowa anymore . . .

Luckily all I had to do was take a shuttle bus to my hotel and English is the international language of tourism, so my first few hours in Japan weren't so daunting. The whole trip had been arranged by one of my uncles who spent a lot of time in Japan on business. His contacts there had helped arrange the trip and even gave me a ride up to Yoshihara's shop.

Yoshihara's shop complex was a hour north of Tokyo set in the middle of a lettuce field. There was the shop, a storage building for charcoal and rice straw, and a small house. His primary residence is in Tokyo and he only went there once a month to do the heavy forging. Japanese swordmaking is regulated by the government and consequently the output of all licenced swordmakers is restricted to set quantities. This measure is intended to keep a high level of quality in the work. Because he can only make so many blades a month, Yoshihara spends a week up at this shop, where there are no noise restrictions, doing all of the work that requires his large trip hammers. Once the steel is worked to the proper consistency and forged into a sword blank, he can do the rest of the process at his other shop in Tokyo.

While Yoshihara worked, I documented the process. Yazu, Yoshihara's current apprentice squatted near the forge watching Yoshihara work and I sat next to him. My western legs weren't conditioned to squat for a long time so my hosts provided me with a chair which sat maybe eight inches off the ground. It wasn't too comfortable either, so I would alternate between squatting and sitting, all the while taking furious notes and pictures.

Prior to this I had spent the summer working with my friend trying to figure out the process. We read the few books available in English (the most complete of which was written by Yoshihara's brother) and watching youtube videos. We put an anvil on the floor and stacked firebrick in an old Champion 400 forge to emulate a Japanese style forge. I cut apart a few old drive shafts and my friend made handles so we could have some Japanese pattern sledge hammers. We billeted and welded all of the high-carbon scrap that I had been accumulating as we attempted to figure out the process. I had almost everyone in the shop swinging a hammer -interns, volunteers, employees, everyone was into the project. The finished billets were worked into paring chisels which I will probably post about later.

Squatting next to Yoshihara's forge, watching the real deal was amazing. Much of our hard work was vindicated. Things we had figured out and even some things we had guessed at were confirmed. But there was so much more too, and I remember thinking that I should have spent some time conditioning my writing hand in preparation for this trip -I couldn't take notes fast enough!

More to come in Part 2

Japan was probably my most intense experience. I've traveled internationally before, but never to Asia. In Europe, it seemed like I could get a feel for parts of the different languages I heard, most share certain words or wood roots, but the Japanese language seemed like white noise to my ears, and when you get off an eleven hour flight, it's mid-night at Narita Airport and you're alone, you realize pretty quickly that you aren't in Iowa anymore . . .

Luckily all I had to do was take a shuttle bus to my hotel and English is the international language of tourism, so my first few hours in Japan weren't so daunting. The whole trip had been arranged by one of my uncles who spent a lot of time in Japan on business. His contacts there had helped arrange the trip and even gave me a ride up to Yoshihara's shop.

|

| Left to right: Yoshihara-san, me, Yazu (Yoshihara's apprentice) |

While Yoshihara worked, I documented the process. Yazu, Yoshihara's current apprentice squatted near the forge watching Yoshihara work and I sat next to him. My western legs weren't conditioned to squat for a long time so my hosts provided me with a chair which sat maybe eight inches off the ground. It wasn't too comfortable either, so I would alternate between squatting and sitting, all the while taking furious notes and pictures.

Prior to this I had spent the summer working with my friend trying to figure out the process. We read the few books available in English (the most complete of which was written by Yoshihara's brother) and watching youtube videos. We put an anvil on the floor and stacked firebrick in an old Champion 400 forge to emulate a Japanese style forge. I cut apart a few old drive shafts and my friend made handles so we could have some Japanese pattern sledge hammers. We billeted and welded all of the high-carbon scrap that I had been accumulating as we attempted to figure out the process. I had almost everyone in the shop swinging a hammer -interns, volunteers, employees, everyone was into the project. The finished billets were worked into paring chisels which I will probably post about later.

Squatting next to Yoshihara's forge, watching the real deal was amazing. Much of our hard work was vindicated. Things we had figured out and even some things we had guessed at were confirmed. But there was so much more too, and I remember thinking that I should have spent some time conditioning my writing hand in preparation for this trip -I couldn't take notes fast enough!

More to come in Part 2

Tenon Saws

Here are pictures from my latest tenon saws. For one I was working with a really old pattern, not only the rounded cheeks that I like so much, but with a style of fasteners predating the brass split nuts.

I replicated the castellated style of nuts used on a few of the early to mid 1700 saws that exist in several museum's collections. I couldn't bring myself to peen the rivet end into place, so I did an experiment with fine threads. Looking through my books I am aware of three saws that have this style. The White saw in the collections of the Stanley-Whitman House; a William Smith pictured in Tools for Working Wood In Eighteenth Century America, by Jay Gaynor; and this one pictured in Classic Hand Tools, by Garrett Hack.

The rivets on the saw from Hack's book are hard to see, but they are definitely square. They may or may not have the decorative filings that appear on the Smith saw (I also have it on very good authority that the White saw has the same style).

One of these days I'll make a saw and rivet it in place, but in the meantime, I'll stick to the split nuts.

Gaynor, James M., and Nancy L. Hagedorn. Tools: Working Wood in Eighteenth-Century America. Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, 1993.

Hack, Garrett. Classic Hand Tools. Newtown, Conn.: Taunton Press, 1999.

|

| Left side |

|

| Right side - castellated style of nuts |

|

| White Tenon Saw |

|

| William Smith (1718-1750) replacement handle |

|

| Hack |

|

| Smith saw rivets close-up |

|

| Dad's Christmas present -18in tenon saw |

Gaynor, James M., and Nancy L. Hagedorn. Tools: Working Wood in Eighteenth-Century America. Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, 1993.

Hack, Garrett. Classic Hand Tools. Newtown, Conn.: Taunton Press, 1999.

Monday, January 23, 2012

Williamsburg

For the summer of 2011 I took a working vacation. I'd been out of the museum world just long enough to miss parts of it, but don't mistake a sense of altruism for my true motivations -I wanted the chance to work with these guys.

If you've read my "About Me" section you know that my background consists of working with my dad in his machine shop, supervising a museum blacksmith shop, and spending some time living and studying with Japanese swordsmith Shoji Yoshihara. My real experiences are in metal working, but when I applied to Williamsburg, I stated that I was interested in woodworking. Truthfully I am interested in both but coinciding with this is my desire to make all of my own tools. My forge is full of tongs and other tools I've replicated, but my wood shop is not nearly as well equiped. I went to Williamsburg to work with the guys that use accurate replicas of tools from a period of time when these things were approaching incredible levels of beauty and mechanical excellence. I wanted to know what was good, and what was bad (any survey of tool history will show you there were always "bumps" in the road of technological evolution) and pick up whatever woodworking tips I could glean in the meantime.

I don't think I was your typical intern. Certainly I was a novice to woodworking, but I did know a few things, and that allowed me to jump right into my first project, making the shop a copy of the router from the Seaton Chest. The master of the shop, Mack Headley, went to one of his many stashes of wood and brought back a section of beech, 6"x6"x72" or so and suggested that it might be better to make two at the same time -it would be better for sticking the ogee into the front if done on a piece two times, and then some, longer than a single. Resawing that big boy was fun, and I say this in all seriousness, how could you not have fun using a 4tpi rip saw?

My second project was replicating a mitre plane. I'm aware that there is discussion and even argument in a few circles about the terminology, etymology, and any other epistemological aspect relating to what constitutes a mitre plane and what consitutes a strike block -so here's the definition we worked with: A mitre plan is a bevel up plane bedded at a very low angle 20-22.5 degrees while a stike block is bevel down, and typically bedded at 35-36 degrees. Both are appropriate for a colonial American shop and the originals for the projects were taken from CW's collections.

The mitre plane I copied was from the Carwright Chest. The chest is a motley assortment of woodworking tools which may not represent the personal tools of a cabinetmaker, but might be an assemblage of tools bought by someone collecting them piecemeal. Whatever the reasons for this eccentric collection, it contains some gems like the mitre plane. The original was made by sawing off one cheek, then probably sawing the bed and abutments. The cheek was then glued back on and the bed was trued and the blade and wedge fitted. This unconventional method of construction is probably just another one of those "bumps" in tool history and may or may not have been a "one off" craftsman-made item. The reproduction I made would not be made with the same method, instead I chiseled, drilled, and floated the bed down.

Next was the strike block, patterned off of a John Green. While this project was a bit more conventional, it required some tricky work in replicating the tight throat extending upwards for 3/8in or so. On your standard bench-type planes this design would clog quickly, but remember strike blocks are intended mostly for end grain and generally produce very small shavings. Having this narrow throat also allows the user to true up the bed several times without opening the mouth too much.

My last few projects were making a few keyhole saw blades with a few different tooth geometries and a copy of a Kenyon compass saw which I ran out of time on.

Working at the Hay Shop was another great opportunity to spend a few months worth of quality hands-on time with some very talented woodworkers. Very few places offer people the opportunity to pursue historical trades with such support and encouragement as Colonial Williamsburg does and I am grateful for the chance to be involved in their efforts to understand the tools and methods used by 18th century cabinetmakers. Thanks again, guys.

If you've read my "About Me" section you know that my background consists of working with my dad in his machine shop, supervising a museum blacksmith shop, and spending some time living and studying with Japanese swordsmith Shoji Yoshihara. My real experiences are in metal working, but when I applied to Williamsburg, I stated that I was interested in woodworking. Truthfully I am interested in both but coinciding with this is my desire to make all of my own tools. My forge is full of tongs and other tools I've replicated, but my wood shop is not nearly as well equiped. I went to Williamsburg to work with the guys that use accurate replicas of tools from a period of time when these things were approaching incredible levels of beauty and mechanical excellence. I wanted to know what was good, and what was bad (any survey of tool history will show you there were always "bumps" in the road of technological evolution) and pick up whatever woodworking tips I could glean in the meantime.

I don't think I was your typical intern. Certainly I was a novice to woodworking, but I did know a few things, and that allowed me to jump right into my first project, making the shop a copy of the router from the Seaton Chest. The master of the shop, Mack Headley, went to one of his many stashes of wood and brought back a section of beech, 6"x6"x72" or so and suggested that it might be better to make two at the same time -it would be better for sticking the ogee into the front if done on a piece two times, and then some, longer than a single. Resawing that big boy was fun, and I say this in all seriousness, how could you not have fun using a 4tpi rip saw?

My second project was replicating a mitre plane. I'm aware that there is discussion and even argument in a few circles about the terminology, etymology, and any other epistemological aspect relating to what constitutes a mitre plane and what consitutes a strike block -so here's the definition we worked with: A mitre plan is a bevel up plane bedded at a very low angle 20-22.5 degrees while a stike block is bevel down, and typically bedded at 35-36 degrees. Both are appropriate for a colonial American shop and the originals for the projects were taken from CW's collections.

The mitre plane I copied was from the Carwright Chest. The chest is a motley assortment of woodworking tools which may not represent the personal tools of a cabinetmaker, but might be an assemblage of tools bought by someone collecting them piecemeal. Whatever the reasons for this eccentric collection, it contains some gems like the mitre plane. The original was made by sawing off one cheek, then probably sawing the bed and abutments. The cheek was then glued back on and the bed was trued and the blade and wedge fitted. This unconventional method of construction is probably just another one of those "bumps" in tool history and may or may not have been a "one off" craftsman-made item. The reproduction I made would not be made with the same method, instead I chiseled, drilled, and floated the bed down.

Next was the strike block, patterned off of a John Green. While this project was a bit more conventional, it required some tricky work in replicating the tight throat extending upwards for 3/8in or so. On your standard bench-type planes this design would clog quickly, but remember strike blocks are intended mostly for end grain and generally produce very small shavings. Having this narrow throat also allows the user to true up the bed several times without opening the mouth too much.

|

| Left to right: Routers, Strike Block, Mitre Plane, Compass Saw |

Working at the Hay Shop was another great opportunity to spend a few months worth of quality hands-on time with some very talented woodworkers. Very few places offer people the opportunity to pursue historical trades with such support and encouragement as Colonial Williamsburg does and I am grateful for the chance to be involved in their efforts to understand the tools and methods used by 18th century cabinetmakers. Thanks again, guys.

|

| Anthony Hay Shop 2011 - Left to Right: Brian Weldy, Ed Wright, Kaare Loftheim, Mack Headley, Sam Cady, Bill Pavlack |

Sunday, January 22, 2012

Preview

Now that I have my process fairly streamlined, I want to work on some new designs. This post will show you what I have in the "R&D" phase.

Working with that rounded cheek design, putting the handle a bit lower, and experimenting with a fastener design that likely came before the split nuts. Earlier saws had their handles riveted to the blades. I'd like to replicate this look, yet still allow the handle to come off without significant alterations having to be made. One solution seems promising, but I want to do a large amount of field testing before I unleash this on the public.

Compass saws are something that I think will experience a resurgence in interest some day. They are useful, but only when you find a good one. If you prowl antique stores you know that most of the surviving ones are often kinked. I think this is probably a combination of poor maintenance (not sharpening) and then misuse (exerting too much force with a dull blade). Traditionally they were made with thicker blades taper ground on two axises and employed no set. It's hard to do a comparison to see how their manufacture changed over time unless you have a large collection of them. I do not, and I get funny looks when I take my calipers into antique stores. However I'm fairly certain that the blade thickness decreased between the eighteenth and twentieth centuries and that manufacturers moved towards setting the teeth; a necessary move, otherwise it would have been very easy to kink such a blade.

I also want to play around with table saws. Just from meditating on the subject I have a few notions about why the table saws were just a blip on the radar of saws but I want to test these theories out. Again I don't have a large body of artifacts to study, so I'm relying on research to help me out. Ed Lebetkin who runs the the Woodwright Tool Store above the Woodwright School has been very helpful in providing me with measurements and observations about the ones that he has in inventory. The details of Ed's observations are pretty interesting, but that will all come out in another post.

I also want to play around with table saws. Just from meditating on the subject I have a few notions about why the table saws were just a blip on the radar of saws but I want to test these theories out. Again I don't have a large body of artifacts to study, so I'm relying on research to help me out. Ed Lebetkin who runs the the Woodwright Tool Store above the Woodwright School has been very helpful in providing me with measurements and observations about the ones that he has in inventory. The details of Ed's observations are pretty interesting, but that will all come out in another post.

Labels:

Compass Saw,

Table Saw,

Tenon Saw

Sunday, January 15, 2012

Forge

I made mention in other sections about my metalworking background. This post will showcase some of what I have done. Above is the forge I built for myself after returning from Japan during the winter of 2009-2010. That winter was especially cold in Iowa and I remember a few nights when I had to wash out my mortar pan in below 0 windchills.

The design of the forge is based on a forge built in the 1890s in a small town a half-hour drive from my home. The shop ran from the 1890s until one day in 1940 when the owner closed shop, went home, and passed away. His family kept the doors closed on the shop and when they donated it to the State Historical Society in 1980, it was still just as Mr. Edel had left it the night he closed it up.

The Edel shop is to blacksmiths what the Dominy shop is to woodworkers. It is amazing to tour too for there are a great many things that Mr. Edel built for himself, such as his helve-hammer.

My forge drew upon elements of Edel's forge, and other features that I like in a forge. It is a bottom draft with a deep trough framed together from 8x8 oak. The chimney is brick with a stainless steel flue integrated into it so that I can close it and retain heat when the forge is not in use. Above the ceiling the brick transitions into 12in double wall stainless steel pipe.

My air delivery system is a post all to itself that will probably come later so for now I'll just put up some more pictures.

|

| The forge |

The design of the forge is based on a forge built in the 1890s in a small town a half-hour drive from my home. The shop ran from the 1890s until one day in 1940 when the owner closed shop, went home, and passed away. His family kept the doors closed on the shop and when they donated it to the State Historical Society in 1980, it was still just as Mr. Edel had left it the night he closed it up.

The Edel shop is to blacksmiths what the Dominy shop is to woodworkers. It is amazing to tour too for there are a great many things that Mr. Edel built for himself, such as his helve-hammer.

My forge drew upon elements of Edel's forge, and other features that I like in a forge. It is a bottom draft with a deep trough framed together from 8x8 oak. The chimney is brick with a stainless steel flue integrated into it so that I can close it and retain heat when the forge is not in use. Above the ceiling the brick transitions into 12in double wall stainless steel pipe.

My air delivery system is a post all to itself that will probably come later so for now I'll just put up some more pictures.

|

| Some of the tongs I made to outfit my shop |

|

| It's hard to find good hammers, so I made myself a straight peen 4lb |

|

| Also not impressed with most commerical clinker-breakers, so my dad and I made this |

|

| Controls for electric blower -top lever controls restrictor and escape valves to regulate air flow, bottom controls selector valve between electric blower and bellows. |

My shop is fairly well outfitted, I also have a propane forge and various other tools. But I have to say the one thing I used to have but now miss desperately is interns. You can have all of the swages, dies, and mechanical aids in the world, but nothing is as helpful as an intern trained to be a striker. When I ran the museum shop I had help most days and in those conditions you realize that your work is much easier and accurate with a second pair of hands.

Labels:

Forge

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)